Words & Photos by Hansi Johnson

The recent GRATEFUL DEAD documentary "Long Strange Trip" featured an interview with one of their roadies from the "Wall of Sound" era–when they used the PA and speaker system that was the size of a small town. He reflected on the chaotic and unhinged ordeal of transporting the equipment from place to place and getting it set up by showtime, and how when the police, venue managers, etc. asked the inevitable question, "Who's in charge around here?", they're response was always, "THE SITUATION IS THE BOSS, MAN." We couldn't help but wonder how many times the adventurers in our orbit have felt the same way in the situations they've found themselves in. Here’s one from our pal, Hansi Johnson.

The riches of youth are best wasted on frivolous things.

Our plan was to see how fast we could paddle the Border Route's length of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area. Light, fast, and in a minimalist fashion. It was 2001, and the world had just shifted on its axis after the horrible impacts of the attack on the Twin Towers.

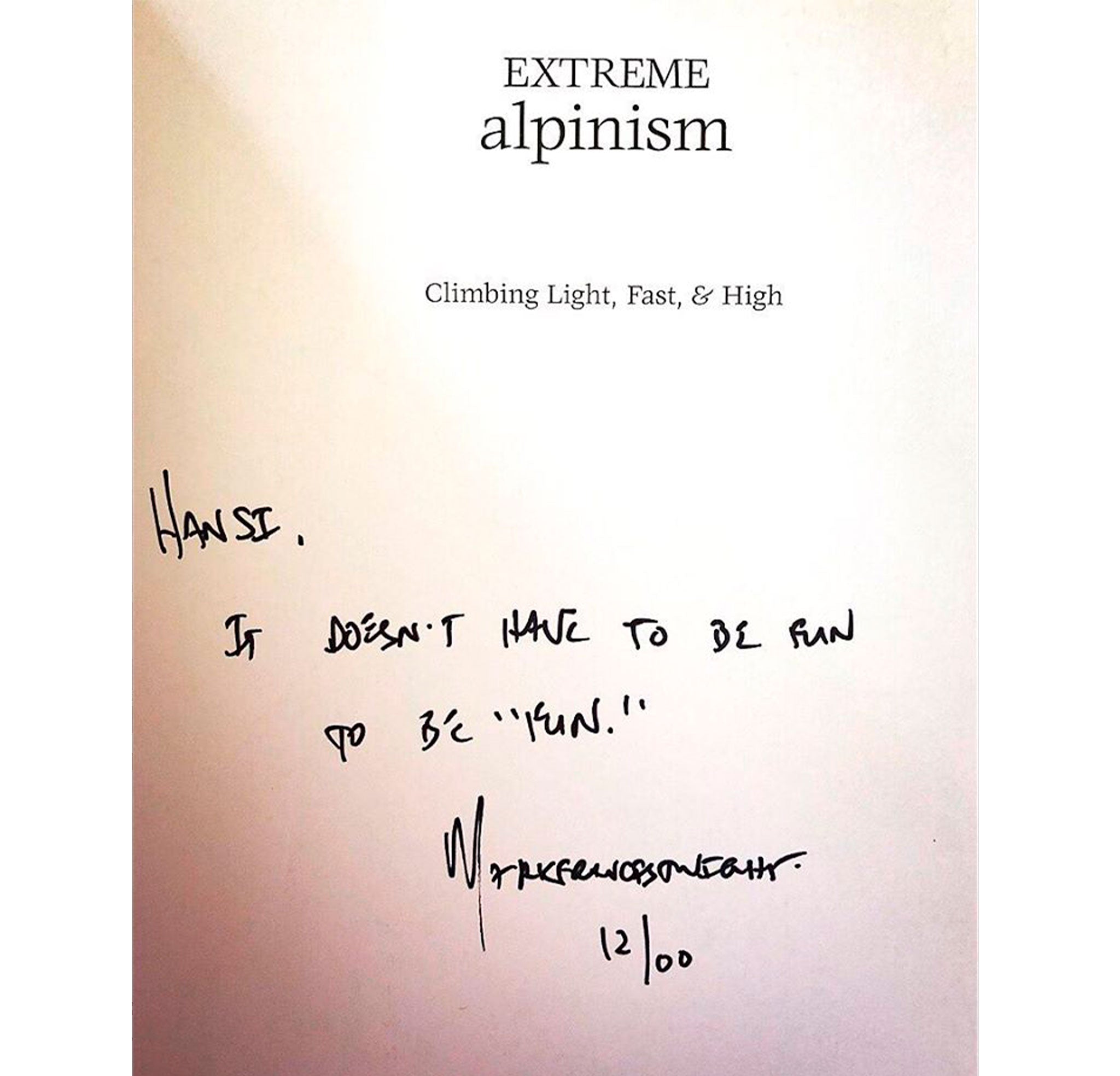

The climber Mark Twight had just released his legendary book called "Extreme Alpinism" the year before. I was not an Alpinist, but I took his point to heart–that to travel fast in the backcountry, less is best regardless of how you are doing it.

Mark is called the "Dark Knight of Climbing," because he was most interested in the blackest space between pleasure and pain. This was a space I could relate to at the time, as could my buddy Guy Evans.

I grew up racing canoes for Wenonah Canoe. My early youth had been spent paddling thousands of hours crammed in a nimble and unforgiving canoe, cranking out mile after mile after mile at 60 strokes a minute. Races of 90 to 100 miles were common, so I could wrap my head around this mission. Guy had been climbing at an elite level for years and was no stranger to sleep deprivation, discomfort, and physical exhaustion himself. He was a perfect partner for this crime.

We originally wanted to make our attempt in the summer when the light was longest and the weather the most amenable, but life that summer had other plans. The only window of time for the two of us came in early October, so we took it.

The 260-mile route is usually traveled by folks in 12-13 days of straight paddling, Guy, and I wanted to do it in four or less.

We had a day pack between us. It was mainly filled with high energy food. However, at the last minute, we had to admit that it was October in Northern Minnesota and that maybe it would be a good idea to pack a small one-person tent and a tiny Polish alpinist stove that Guy used on alpine climbing missions in case of emergency.

We kicked off the ass-kicking with decent weather and made amazing time for the first 10 hours. That was when Mother Nature decided it was time to reach down and rub our faces firmly into the dirt.

It started with super high winds (luckily going our way), but then the temps plummeted. We went from the 50's to the high 20's in a couple of hours.

The snow came with the darkness. The fight is always toughest when viewed through the cone of a dim headlamp with snowflakes freezing your eyes shut. At first, we just shrugged it off as a squall and kept our speed up. After a while, though, it became apparent this was not a squall but a full-fledged storm. The snow started to pile up. Footing on portages became challenging. Our clothes were wetting out, and our energy levels started to wane.

Finally, we realized we needed to shelter out for a while to warm back up and get some hot calories in us. We pitched our tent on a portage and hopped in, two guys in a tiny one-person tent. While we tried to warm up, Guy decided to use the small stove to heat some water. This stove looked like it had come straight out of the cold war. It was tiny but simple, but of course, as archaic as the Soviet Union. We propped it up in the doorway of the tent and used our frozen hands to attempt to fire it up. At first, it sputtered and went out. A dismayed Guy gave it more gas and went for it with the lighter. Instead of sputtering this time, it just flared up into a giant ball of flame, threatening to start the whole tent on fire with us in it—a human Crème Brule with a mushy center.

Thinking fast, Guy booted the stove out into the darkness and dumping snow where it spiraled down the portage trail and disappeared.

No hot food today, boys.

At this point, we were basically at the mercy of the weather. With the snowstorm and the night, we were powerless.

So, we just hunkered down and waited it out. We ate and slept for several hours, then luckily the storm cleared, the storm front passed, and with it came more high winds and clear cold skies.

Off weather's hook, we set off and continued on our journey with no real issues, eventually meeting our goal and finishing in roughly four days. With a little fortitude and good luck, the situation became ours to control once more!

Hansi Johnson is the Director of Recreational Lands for the Minnesota Land Trust. Based near the outdoors mecca of Duluth, Johnson has spent a lifetime Nordic ski racing, paddling, casting, hunting, shooting photos, and pedaling all over the globe. You can follow some of his award-winning photography at instagram.com/hansski43/