Words by Brad Meiklejohn

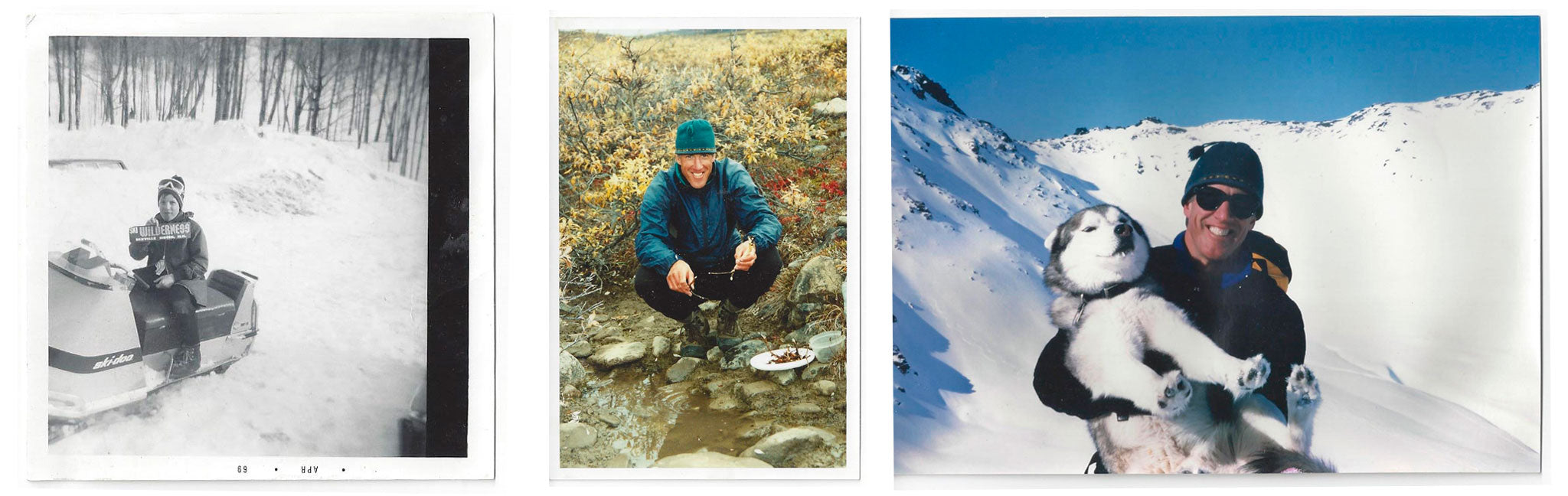

A recent news story described me as “an aging adventurer.” After my initial indignation, I checked the mirror and seeing age 58 reflected, I had to agree. Better distinguished than extinguished, I suppose. We are all getting older.

I never thought that I would live this long. I’ve been a skier, climber, packrafter, and explorer since I could walk. I’ve lost 32 friends and family members to avalanches, rock falls, crevasse falls, just plain falls and drownings. They say my friends died doing what they loved. I doubt any of them loved having their necks and backs broken, having their lungs filled with snow and water or having their heads smashed in by rocks. No powder, peak or pour-over is ever worth dying for.

“I am glad I shall never be young without wild country to be young in. Of what avail are forty freedoms without a blank spot on the map?”

It’s not that I have been any smarter or better than any of them, just luckier. I was never deliberately reckless, but I survived the immortal Superman phase of my life just barely. It’s easy to die young doing what you love; James Dean spawned a whole cemetery of outdoor heroes. Nowadays I most admire those who have done what they love their whole lives and died peacefully in bed at a ripe old age.

Birth is the leading cause of death - none of us are getting out of here alive. The greater fear for me has never been of dying, but of not living. On the Loose, the book that most shaped my life, is best summed up as “Get busy living or get busy dying.” I started out chasing crayfish and brook trout in tiny New England streams and my sneakers have stayed wet and muddy ever since.

Growing up in the wild, and never growing up, have made all the difference.

“Does it teach you anything? Like determination? Invention? Improvisation? Foresight? Hindsight? Strength or patience or accuracy or quickness or tolerance or Which wood will burn and how long is a day and how far is a mile And how delicious is water and smoky green pea soup? And how to rely on your Self?”

It is wilderness that built us and wilderness that we evolved to inhabit. Only in the past two hundred years have we moved into a strange new world that we are not designed for. It’s no wonder that depression, anxiety, dissatisfaction, and prescription drug use is soaring. We now use recreation to re-create a semblance of the lives that we are built to live.

For years, my happiness was a function of what I was going to do, what I was doing, or what I had just done. I could be elated after a gorgeous powder day or a challenging whitewater run, and pacing the cage the next day. Climbers talk about feeding the rat, and Roman Dial has a great podcast on the similarity between drugs and adventure. “I used to do a little but a little was too little so then I did a little more” sang Axl Rose, who didn’t shred the gnar before his drug overdose, but he sure talked like us.

Suicide-by-adventure claimed a few of my friends, plain suicide got others, and it nearly got me. I have been to the depths of insatiable craving. The next hit (trip, climb, run) always held the promise of lasting happiness but always failed to deliver. I lived an “if only” story that never came true. “If only this trip wouldn’t end, if only I didn’t have to work, if only I could ski/climb/paddle that fill-in-the-blank.” If your happiness depends on anything at all, you will never be happy.

The good news is, there is another way. My dedication to Buddhist meditation has helped me see that no outdoor adventure, in fact no thing, can ever provide lasting happiness. I no longer have to do anything to be happy, which is handy as I get older. The indoor adventure is the best trip yet.

I still get out, and I try to stay out. It’s not the achievement I am after but the immersion. I want to pay homage to a place more than dominate or simply pass through it. I like to understand how the place works, which means stopping to watch, listen, taste, smell, feel, and consider it. Our senses evolved to thrive in wilderness, but the signals they receive are easily swamped by modern noise. I find it hard to fully arrive in a place in less than a week. The first three days are spent reconnecting with my senses, and the last three days I’m already leaning forward into re-entry.

A Hopi elder told me that the hardest way is the best way. That makes sense to me. “Convenience is the enemy” is one of my favorite bumper stickers seen years ago on a beat down Ford pick-up. Taking the harder way is a course in strategic frustration, a de-conditioning of our relentless and unquenchable desires for comfort and ease. We don’t learn much from comfort; it’s the discomfort that really teaches us. Like how little we really need and how much we can actually put up with.

I am always grateful for everything that I leave behind. “You pack your insecurities,” says Roman. The less stuff you bring the freer your mind is to be engaged with the place, not fiddling and packing and unpacking. This was never more manifest for me than on a minimalist self-support packraft trip down the Grand Canyon in which we bathed in the glory of the canyon rather than schlepping tables, coolers and bocce balls up the beach mornings and afternoons. I think it is a shame that the greatest river trip in the world has been reduced to a bacchanalian luxury cruise.

It’s not dramatic to say that wilderness is nearly gone, like the closed frontier. The blank spots on the map are mostly filled in. While it’s some consolation to say “I knew you when” it doesn’t ease the grief. I’ll keep looking for the last ones, the ones that take weeks to cross without seeing, smelling, hearing, or stepping in the bright spoor of man. But man and woman have converted 77% of the planet to his and her needs, and there are precious few places that exist just for their own sake. Even designated “Wilderness” has to justify itself, for recreation, for renewal, for resources.

My career in conservation was never a choice. I’ve seen too much and know too much about what we have lost to be anything but a conservationist. “The curse of an ecologist is to be aware in a world of wounds,” said Aldo Leopold, more or less. Wilderness shaped me, and I’ve done my little part to keep a few pieces of it together.

A lot of hard work goes into protecting even an acre, and it has taken legions over decades to create the vast parks and wild areas that are the backdrops for our adventures. Small actions matter, so if you feel helpless, remember that action is the best remedy for anxiety. Just as with any adventure, the important thing is to start and continue.